Celtic polytheism (also called Druidic polytheism) is the term for the religious beliefs and practices of the ancient Celts.

Extent of Celtic polytheism

As the religion of the ancient Celts, the shifts in the fortunes of Celtic Polytheism coincided with those of its people. The Celts, like other ancient Indo-European peoples, practised a form of polytheism, which reached the apogee of its influence and territorial expansion during the 4th century BC, extending across the length of Europe from Great Britain to Asia Minor.

From the 3rd century BC onward their history is one of decline and disintegration, and with Julius Caesar's conquest of Gaul (58 –51 BC) Celtic independence came to an end on the European continent. In Great Britain]] and Ireland this decline moved more slowly, but traditional culture was gradually eroded through the pressures of political subjugation; today the Celtic languages are spoken only on Western Europe, in restricted areas of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and Brittany (in this last instance largely as a result of immigration from Britain from the 4th century to the 7th century AD). It is not surprising, therefore, that the unsettled and uneven history of the Celts has affected the documentation of their culture and religion.

Research

Three main types of sources provide information on Celtic polytheism: the minted coins of Gaul, the sculptural monuments associated with the Celts of continental Europe and of Roman Britain, and the insular literatures of Celtic mythology that have survived in writing from medieval times. All pose problems of interpretation. The pre-Roman coins of the 1st century BC and early 1st century AD bear no inscriptions, and their iconography derives partly from standardized Hellenistic numismatic prototypes and partly presents highly local emblems. Most of the monuments, and their accompanying inscriptions, belong to the Roman period and reflect a considerable degree of syncretism between Celtic and Roman gods; even where figures and motifs appear to derive from pre-Roman tradition, they are difficult to interpret in the absence of a preserved literature on mythology.

Only after the lapse of many centuries—beginning in the 7th century in Ireland, even later in Wales—was the mythological tradition consigned to writing, but by then Ireland and Wales had been Christianized and the scribes and redactors were monastic scholars. The resulting literature is abundant and varied, but it is much removed in both time and location from its epigraphic and iconographic correlatives on the Continent and inevitably reflects the redactors' selectivity and something of their Christian learning. Given these circumstances it is remarkable that there are so many points of agreement between the insular literatures and the continental evidence. This is particularly notable in the case of the Classical commentators from Poseidonius (c. 135–c. 51 BC) onward who recorded their own or others' observations on the Celts.

Syncretism with other forms of polytheism

The locus classicus for the Celtic gods of Gaul is the passage in Julius Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico (52–51 BC; The Gallic War) in which he names five of them together with their functions. Mercury was the most honoured of all the gods and many images of him were to be found. Mercury was regarded as the inventor of all the arts, the patron of travellers and of merchants, and the most powerful god in matters of commerce and gain. After him the Gauls honoured Apollo, Mars, Jupiter, and Minerva. Of these gods they held almost the same opinions as other peoples did: Apollo drives away diseases, Minerva promotes handicrafts, Jupiter rules the heavens, and Mars controls wars.

In characteristic Roman fashion, however, Caesar does not refer to these figures by their native names but by the names of the Roman gods with which he equated them, a procedure that greatly complicates the task of identifying his Gaulish deities with their counterparts in the insular literatures. He also presents a neat schematic equation of god and function that is quite foreign to the vernacular literary testimony. Yet, given its limitations, his brief catalog is a valuable and essentially accurate witness. In comparing his account with the vernacular literatures, or even with the continental iconography, it is well to recall their disparate contexts and motivations. As has been noted, Caesar's commentary and the iconography refer to quite different stages in the history of Gaulish religion; the iconography of the Roman period belongs to an environment of profound cultural and political change, and the religion it represents may in fact have been less clearly structured than that maintained by the druids (the priestly order) in the time of Gaulish independence.

On the other hand, the lack of structure is sometimes more apparent than real. It has, for instance, been noted that of the several hundred names containing a Celtic element attested in Gaul the majority occur only once, which has led some scholars to conclude that the Celtic gods and their cults were local and tribal rather than national. Supporters of this view cite Lucan's mention of a god Teutates, which they interpret as "god of the tribe" (it is thought that teuta meant "tribe" in Celtic). The seeming multiplicity of deity names may, however, be explained otherwise—for example, many are simply epithets applied to major deities by widely extended cults.

Cosmology and eschatology

Little is known about the religious beliefs of the Celts of Gaul. They believed in a life after death, for they buried food, weapons, and ornaments with the dead. The druids, the early Celtic priesthood, taught the doctrine of transmigration of souls and discussed the nature and power of the gods.

The Irish believed in an otherworld, imagined sometimes as underground and sometimes as islands in the sea. The otherworld was variously called "the Land of the Living," "Delightful Plain," and Tir na nOg "Land of the Young" and was believed to be a country where there was no sickness, old age, or death, where happiness lasted forever, and a hundred years was as one day. It was similar to the Elysium of the Greek mythology and may have belonged to ancient Indo-European tradition. In Celtic eschatology, as noted in Irish vision or voyage tales, a beautiful girl approaches the hero and sings to him of this happy land. He follows her, and they sail away in a boat of glass and are seen no more; or else he returns after a short time to find that all his companions are dead, for he has really been away for hundreds of years. Sometimes the hero sets out on a quest, and a magic mist descends upon him. He finds himself before a palace and enters to find a warrior and a beautiful girl who make him welcome. The warrior may be Manannan mac Lir, or Lugh himself may be the one who receives him, and after strange adventures the hero returns successfully. These Irish tales, some of which date from the 8th century, are infused with the magic quality that is found 400 years later in the Arthurian romances.

Something of this quality is preserved, too, in the Welsh story of Branwen, daughter of Llyr, which ends with the survivors of the great battle feasting in the presence of the severed head of Bran the Blessed, having forgotten all their suffering and sorrow. But this "delightful plain" was not accessible to all. Donn, god of the dead and ancestor of all the Irish, reigned over Tech Duinn, which was imagined as on or under Bull Island off the Beare Peninsula, and to him all men returned except the happy few. This appears in Welsh mythology as Annwfn (from *Andubnion, very deep level) and ruled by seemingly different gods Arawn (*Ariomans) and Gwyn ap Nudd (*Vindos).

Worship

According to Poseidonius and later classical authors Gaulish religion and culture were the concern of three professional classes—the druid, the bards, and between them an order closely associated with the druids that seems to have been best known by the Gaulish term vates, cognate with the Latin vates ("seers"). This threefold hierarchy had its reflex among the two main branches of Celts in Ireland and Wales but is best represented in early Irish tradition with its druids, filidh (singular fili), and bards; the filidh evidently correspond to the Gaulish vates.

The word "druid" is often cited as meaning means "knowing the oak tree" and may derive from druidic ritual, which seems in the early period to have been performed in the forest. Caesar stated that the druids avoided manual labour and paid no taxes, so that many were attracted by these privileges to join the order. They learned great numbers of verses by heart, and some studied for as long as 20 years; they thought it wrong to commit their learning to writing but used the Greek alphabet for other purposes.

Classical sources claimed that the Celts had no temples (before the Gallo-Roman period) and that their ceremonies took place in forest sanctuaries. Archaeology demonstrates this to be incorrect, with a large number of temple sites excavated. In the Gallo-Roman period, more permanent stone temples were erected, and many of them have been discovered by archaeologists in Britain as well as in Gaul.

Celtic polytheism was evidently sacrificial, practising various forms of sacrifice in an attempt to redeem, obligate or appease the gods. Human sacrifice was practiced in Gaul: Cicero, Julius Caesar, Suetonius, and Lucan all refer to it, and Pliny the Elder says that it occurred in Britain, too. It was forbidden under Tiberius and Claudius. There is some evidence that human sacrifice was known in Ireland and was forbidden by St. Patrick.

Religious castes

Druids

A Druid (often cited as being from the Celtic: "Knowing [or Finding] the Oak Tree") was a member of the learned class among the ancient Celts. They seem to have frequented oak forests and acted as priests, teachers, and judges. The earliest known records of the Druids come from the 3rd century BC.

According to Julius Caesar, who is the principal source of information about the Druids, there were two groups of men in Gaul that were held in honour, the Druids and the noblemen (equites). Caesar related that the Druids took charge of public and private sacrifices, and many young men went to them for instruction. They judged all public and private quarrels and decreed penalties. If anyone disobeyed their decree, he was barred from sacrifice, which was considered the gravest of punishments. One Druid was made the chief; upon his death, another was appointed. If, however, several were equal in merit, the Druids voted, although they sometimes resorted to armed violence. Once a year the Druids assembled at a sacred place in the territory of the Carnutes, which was believed to be the centre of all Gaul, and all legal disputes were there submitted to the judgment of the Druids. Caesar also recorded that the Druids abstained from warfare and paid no tribute. Attracted by those privileges, many joined the order voluntarily or were sent by their families. They studied ancient verse, natural philosophy, astronomy, and the lore of the gods, some spending as much as 20 years in training. The Druids' principal doctrine was that the soul was immortal and passed at death from one person into another.

The Druids may have offered human sacrifices for those who were gravely sick or in danger of death in battle. Caesar said that huge wickerwork images were filled with living men and then burned, for which no other evidence has been found. Although the Druids preferred to sacrifice criminals, they would choose innocent victims if necessary. Caesar is the chief authority, but he may have received some of his facts from the Stoic philosopher Poseidonius, whose account is often confirmed by early medieval Irish sagas. Caesar's description of the annual assembly of the Druids and their election of an arch-Druid is also confirmed by an Irish saga. It must be remembered that Caesar was at war with the Celts, and that all information is questionable because much of it was Roman propaganda.

In the early period, Druidic rites were held in clearings in the forest. Sacred buildings were used only later under Roman influence. The Druids were suppressed in Gaul by the Romans under Tiberius (reigned AD 14–37) and probably in Britain a little later. In Ireland they lost their priestly functions after the coming of Christianity and survived as poets, historians, and judges (filid, senchaidi, and brithemain). Many scholars believe that the Hindu Brahmin in the East and the Celtic Druid in the West were lateral survivals of an ancient Indo-European priesthood.

Bards and filid

A bard was a poet, especially one who wrote impassioned, lyrical, or epic verse. Bards were originally Celtic composers of eulogy and satire; the word came to mean more generally a tribal poet-singer gifted in composing and reciting verses on heroes and their deeds. As early as the 1st century AD, the Latin author Lucan referred to bards as the national poets or minstrels of Gaul and Britain. In Gaul the institution gradually disappeared, whereas in Ireland and Wales it survived. The Irish bard through chanting preserved a tradition of poetic eulogy. In Wales, where the word bardd has always been used for poet, the bardic order was codified into distinct grades in the 10th century. Despite a decline of the order toward the end of the European Middle Ages, the Welsh tradition has persisted and is celebrated in the annual eisteddfod, a national assembly of poets and musicians.

The Irish bards seem to have been the filid. A Fili ( Old Irish: "seer", from the Proto-Celtic *welits) was professional poet in ancient Ireland whose official duties were to know and preserve the tales and genealogies and to compose poems recalling the past and present glory of the ruling class. The filid constituted a large aristocratic class, expensive to support, and were severely censured for their extravagant demands on patrons as early as the assembly of Druim Cetta (575); they were defended at the assembly by St. Columba. Their power was not checked, however, since they could enforce their demands by the feared lampoon (áer), or poet's curse, which not only could take away a man's reputation but, according to a widely held ancient belief, could cause physical damage or even death. Although by law a fili could be penalized for abuse of the áer, belief in its powers was strong and continued to modern times.

After the Christianization of Ireland in the 5th century, filid assumed the poetic function of the outlawed Druids, the powerful class of learned men of the pagan Celts. The filid were often associated with monasteries, which were the centres of learning.

Filid were divided into seven grades. One of the lower and less learned grades was bard. The highest grade was the ollamh, achieved after at least 12 years of study, during which the poet mastered more than 300 difficult metres and 250 primary stories and 100 secondary stories. He then could wear a cloak of crimson bird feathers and carry a wand of office. Although at first the filid wrote in a verse form similar to the alliterative verse prevalent in Germanic languages, they later developed intricate rules of prosody and rigid and complicated verse forms, the most popular of which was the debide (modern Irish deibide, "cut in two"), a quatrain composed of two couplets, linked by the rhyme of a stressed syllable with an unstressed one.

After the 6th century, filid were granted land. They were required not only to write official poetry but also to instruct the residents of the area in law, literature, and national history. These seats of learning formed the basis for the later great bardic colleges.

By the 12th century filid were composing lyrical nature poetry and personal poems that praised the human qualities of their patrons, especially their generosity, rather than the patrons' heroic exploits or ancestors. They no longer strictly adhered to set rules of prosody. The distinction between the fili and the bard gradually broke down; the filid had given way to the supremacy of the bards by the 13th century.

Festivals

Insular sources provide important information about Celtic religious festivals. In Ireland the year was divided into two periods of six months by the feasts of Beltane (May 1) and Samhain (Samain; November 1), and each of these periods was equally divided by the feasts of Imbolc (February 1), and Lughnasadh (August 1). Samhain seems originally to have meant "summer," but by the early Irish period it had come to mark summer's end. Beltine is also called Cetsamain ("First Samhain"). Imbolc has been compared by the French scholar Joseph Vendryes to the Roman lustrations and apparently was a feast of purification for the farmers. It was sometimes called oímelc ("sheep milk") with reference to the lambing season. Beltine ("Fire of Bel") was the summer festival, and there is a tradition that on that day the druids drove cattle between two fires as a protection against disease. Lughnasadh was the feast of the god Lugh.

Beltane

Beltane, also spelled Beltine, Irish Beltaine, Beáltaine, or Belltaine and also known as Cétsamain, was a festival held on the first day of May in Ireland and Scotland, celebrating the beginning of summer and open pasturing. Beltane is first mentioned in a glossary attributed to Cormac, bishop of Cashel and king of Munster, who was killed in 908. Cormac describes how cattle were driven between two bonfires on Beltane as a magical means of protecting them from disease before they were led into summer pastures—a custom still observed in Ireland in the 19th century. Other festivities included Maypole dances and cutting of green boughs and flowers.

In early Irish lore a number of significant events took place on Beltane, which long remained the focus of folk traditions and tales in Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. As did other pre-Christian Celtic peoples, the Irish divided the year into two main seasons. Winter and the beginning of the year fell on November 1 (Irish: Samain) and midyear and summer on May 1 (Irish: Beltaine). These two junctures were thought to be critical periods when the bounds between the human and supernatural worlds were temporarily erased; on May Eve witches and fairies roamed freely, and measures had to be taken against their enchantments.

Cormac derives the word Beltaine from the name of a god Bel, or Bil, and the Old Irish word tene, "fire." Despite linguistic difficulties, a number of 20th-century scholars have maintained modified versions of this etymology, linking the first element of the word with the Gaulish god Belenos.

In Ireland, the word "Beáltaine" is generally pronounced /ˈbʲɑlˠ.t̪ˠə.n̪ʲə/ (IPA) or b-YOWL-ten-ah.

Samhain

The beginning of the month of Samhain (Old Irish samain), was one of the most important calendar festivals of the Celtic year. At "the three nights of Samhain", held around the beginning of November, originally at plenilune, the world of the gods was believed to be made visible to mankind, and the gods played many tricks on their mortal worshipers; it was a time fraught with danger, charged with fear, and full of supernatural episodes. Sacrifices and propitiations of every kind were thought to be vital, for without them the Celts believed they could not prevail over the perils of the season or counteract the activities of the deities. Samhain was an important precursor to Halloween.

Cults within Celtic polytheism

The notion of the Celtic pantheon as merely a proliferation of local gods is contradicted by the several well-attested deities whose cults were observed virtually throughout the areas of Celtic settlement.

Cult of Lugus-Mercurius

According to Caesar the god most honoured by the Gauls was "Mercury (Greek: Hermes). ," and this is confirmed by numerous images and inscriptions. His Celtic name is not explicitly stated, but it is clearly implied in the place-name Lugudunon ("the fort or dwelling of the god Lugus") by which his numerous cult centres were known and from which the modern Lyon, Laon, and Loudun in France, Carlisle (formerly Castra Luguvallium, "Fort Strong in the God Lugus"); Leiden in The Netherlands, and Legnica in Poland derive. Clearly Lugus, also called Lug, (from Celtic: *Lug- ambivalently meaning "Lynx," "Oath," "Deceiver" and "Moonlight"), was one of the major gods, whose cult was widespread throughout the early Celtic world . The Irish and Welsh cognates of Lugus are Lugh and Llew, respectively, and the traditions concerning these figures mesh neatly with those of the Gaulish god. Caesar's description of the latter as "the inventor of all the arts" might almost have been a paraphrase of Lugh's conventional epithet sam ildánach ("possessed of many talents"). An episode in the Irish tale of the Battle of Magh Tuiredh is a dramatic exposition of Lugh's claim to be master of all the arts and crafts, and dedicatory inscriptions in Spain and Switzerland, one of them from a guild of shoemakers, commemorate Lugus, or Lugoves, the plural perhaps referring to the god conceived in triple form.

An episode in the Middle Welsh collection of tales called the Mabinogion, (or Mabinogi), seems to echo the connection with shoemaking, for it represents Lleu as working briefly as a skilled exponent of the craft. In Ireland Lugh was the youthful victor over the demonic Balar or Balor "of the venomous eye." He was the divine exemplar of sacral kingship, and his other common epithet, lámhfhada ("of the long arm"), perpetuates an old Indo-European metaphor for a great king extending his rule and sovereignty far afield. His proper festival, called Lughnasadh ("Festival of Lugh") in Ireland, was celebrated—and still is at several locations—in August; at least two of the early festival sites, Carmun and Tailtiu, were the reputed burial places of goddesses associated with the fertility of the earth (as was, evidently, the consort Maia—or Rosmerta ("the Provider")—who accompanies "Mercury" on many Gaulish monuments).

According to Irish tradition, Lug Lámfota ("Lug of the Long Arm") was the sole survivor of triplet brothers all having the same name. At least three dedications to Lugus in plural form, Lugoues, are known from the European continent, and the Celtic affinity for trinitarian forms would suggest that three gods were likewise envisaged in these dedications. Lug's son, or rebirth, according to Irish belief, was the great Ulster hero, Cú Chulainn ("Culann's Dog").

In Wales, as Llew Llaw Gyffes ("Llew of the Dexterous Hand"), he was also believed to have had a strange birth. His mother was the virgin goddess Arianrhod ("Silver Wheel"). When her uncle, the great magician Math, tested her virginity by means of a wand of chastity, she at once gave birth to a boy child, who was instantly carried off by his uncle Gwydion and reared by him. Arianrhod then sought repeatedly to destroy her son, but she was always prevented by Gwydion's powerful magic; she was forced to give her son a name and provide him with arms; finally, as his mother had denied him a wife, Gwydion created a woman for him from flowers.

The variety of the attributes of Lugh Samildánach ("Skilled in All the Arts") and the extent to which his calendar festival Lughnasadh on August 1 was celebrated in Celtic lands indicate that he was one of the most powerful and impressive of all the ancient Celtic deities.

Cults of tribalism lordly power and thunderous force

Teutates, also spelled Toutates (Celtic: "God of the People"), seems to have been an important Celtic deity, one of three mentioned by the Roman poet Lucan in the 1st century AD, the other two being Esus ("Lord") and Taranis ("Thunderer"). According to later commentators, victims sacrificed to Teutates were killed by being plunged headfirst into a vat filled with an unspecified liquid, which may have been ale, a favourite drink of the Celts. Teutates was identified with both the Roman Mercury (Greek Hermes) and Mars (Greek Ares). He is also known from dedications in Britain, where his name was written Toutates. The Irish Tuathal Techtmar, one of the legendary conquerors of Ireland, has a name that comes from an earlier form, *Teuto-valos ("Ruler of the People"); he may have been an eponymous deity of the district that he is reputed to have conquered, but he was probably just another manifestation of the great god Teutates.

The Gaulish god "Mars" illustrates vividly the difficulty of equating individual Roman and Celtic deities. Of two later commentators on Lucan's text, the famous passage in Lucan's Bellum civile mentioning the bloody sacrifices offered to the three Celtic gods Teutates, Esus, and Taranis, one identifies Teutates with Mercury, the other with Mars. The probable explanation of this apparent confusion, which is paralleled elsewhere, is that the Celtic gods are not rigidly compartmentalized in terms of function. Thus "Mercury" as the god of sovereignty may function as a warrior, while "Mars" may function as protector of the tribe, so that either one may plausibly be equated with Teutates.

Cult of radiance or healing

The problem of identification is still more pronounced in the case of the Gaulish "Apollo," for some of his 15 or more epithets may refer to separate deities. The solar connotations of Belenus (from Celtic: *bel-, "shining," "radiant" or "brilliant") would have supported the identification with the Greco-Roman Apollo, or, if that etymology does not hold up, the healing attributes of the same (from Proto-Celtic *belen- "henbane", "intoxicating herb") still suggest his similarity to that Greek deity. Several of his epithets, such as Grannus and Borvo (which are associated etymologically with the notions of "boiling" and "heat," respectively), connect him with healing and especially with the therapeutic powers of thermal and other springs, an area of religious belief that retained much of its ancient vigour in Celtic lands throughout the Middle Ages and even to the present time.

Cult of youthful masculinity

Maponos ("Divine Son" or "Divine Youth") is attested in Gaul but occurs mainly in northern Britain. He appears in medieval Welsh literature as Mabon, son of Modron (that is, of Matrona, "Divine Mother"), and he evidently figured in a myth of the infant god carried off from his mother when three nights old. His name survives in Arthurian romance under the forms Mabon, Mabuz, and Mabonagrain. His Irish equivalent was Mac ind Óg ("Young Son" or "Young Lad"), known also as Oenghus or Angus, who dwelt in Bruigh na Bóinne, the great Neolithic, and therefore pre-Celtic, passage grave of Newgrange (or Newgrange House). He was the son of Dagda (or Daghda), chief god of the Irish, and of Boann, the personified sacred river of Irish tradition. In the literature the Divine Son tends to figure in the role of trickster and lover.

Cult of thermal spring-water

There are dedications to "Minerva" in Britain and throughout the Celtic areas of the Continent. At Bath Minerva was identified with the goddess Sulis, whose cult there centred on the thermal springs. Through the plural form Suleviae, found at Bath and elsewhere.

Cult of impressiveness

Ogmios (from Celtic *Ogmio- ‘furrow-maker,’ ‘impresser.’) was apparently a Celtic embodiment of ‘impressiveness’ both literal, as with the impressing action of ploughing and carving symbols, and figurative, as with the impressive nature of eloquence and prowess in warfare. In Gaul, he was identified with the Roman Hercules. He was portrayed as an old man with swarthy skin and armed with a bow and club. He was also a god of eloquence, and in that aspect he was represented as drawing along a company of men whose ears were chained to his tongue.

Ogmios' Irish equivalent was Ogma, whose Herculean, warlike aspect was also stressed. In Irish tradition he was impressively portrayed as a swarthy man whose battle ardour was so great that he had to be controlled by chains held by other warriors until the right moment. Ogham script, an Irish writing system dating from the 4th century AD, seems to have been named after him, a fitting association for a god of eloquence. Impressiveness being an aspect of eloquence, he was seen as a psychopomp, presumably by association with words spoken at funerary rituals.

Cult of exaltedness

Brigantia (Celtic: Highness), known variously Brighid, Bride, or Brigit seems to have embodied Exaltedness and so was the goddess of all such things considered exalted as the poetic arts, crafts, prophecy, healing, wisdom, homely fires, traditional learning, rivers, hills and divination; she was the equivalent of the Roman goddess Minerva (Greek Athena). In Ireland this Brigit was one of three goddesses of the same name, daughters of the Dagda, the great god of that country. Her two sisters were connected with healing and with the craft of the smith. Brigit was worshipped by the semi-sacred poetic class, the filid, who also had certain priestly functions.

Brigit was taken over into Christianity as St. Brigit, but she retained her strong pastoral associations. Her feast day was February 1, which was also the date of the pagan festival of Imbolc, the season when the ewes came into milk. St. Brigit had a great establishment at Kildare in Ireland that was probably founded on a pagan sanctuary. Her sacred fire there burned continually; it was tended by a series of 19 nuns and by the saint herself every 20th day. Brigit still plays an important role in modern Scottish folk tradition, where she figures as the midwife of the Virgin Mary. Numerous holy wells are dedicated to her.

Brigantia, patron goddess of the Brigantes of northern Britain, is substantially the same goddess as Brigit. Her connection with water is shown by her invocation in Roman times as "the nymph goddess"; several rivers in Britain and Ireland are named after her. Her name is cognate with that of Briganti, Latin Brigantia and, as the tutelary goddess of the Brigantes of Britain, there is some onomastic evidence that her cult was known on the Continent, whence the Brigantes had migrated.

Cult of Sucellos

The Gaulish Sucellos (or Sucellus), possibly meaning "the Good Striker," appears on a number of reliefs and statuettes with a mallet as his attribute. He has been equated with the Irish Dagda, "the Good God," also called Eochaidh Ollathair ("Eochaidh the Great Father"). A powerful and widely worshiped Celtic god, his iconographic symbols were usually his mallet and libation saucer, indicative of his powers of protection and provision. His Irish equivalent seeming to have been the Dagda, Sucellus was possibly one of the Gaulish gods who were equated by Julius Caesar with the Roman god Dis Pater, from whom, according to Caesar, all the Gauls believed themselves to be descended. Sucellus was sometimes portrayed with a cask of liquid or with a drinking vessel, which may indicate that he was one of the gods who presided at the otherworld feast. He was also often accompanied by a dog. In Irish forms of his cult, Eochaid Ollathair ("Eochaid the All-Father") , or In Ruad Ro-fhessa ("Red [or Mighty] One of Great Wisdom"), the Dagda ( Celtic"Good God") is one of the leaders of the Irish pantheon, the Tuatha Dé Danann ("People of the Goddess Danu"). The Dagda was credited with many powers and possessed a caldron that was never empty, fruit trees that were never barren, and two pigs—one live and the other perpetually roasting. He also had a huge club that had the power both to kill men and to restore them to life. With his harp, which played by itself, he summoned the seasons. The Dagda mated with the sinister war goddess Morrígan.

Cults of maritime forces

Whereas Ireland had its god of the sea, Manannán mac Lir ("Manannan, son of the Ocean"), and a more shadowy predecessor called Tethra, there is no clear evidence for a Gaulish sea-god, perhaps because the original central European homeland of the Celts had been landlocked.

The Irish sea god Manannan, from whom the name of the Isle of Man allegedly derived. Manannán traditionally ruled an island paradise, protected sailors, and provided abundant crops. He gave immortality to the gods through his swine, which returned to life when killed; those who ate of the swine never died. He wore impenetrable armour and, carrying an invincible sword, rode over the waves in a splendid chariot. He and his Welsh equivalent, Manawydan, brother of the god Brân, are apparently derived from an early unattested Celtic deity, *Manavos "Hand God," or perhaps even from the Proto-Indo-European sacrificer-god, *Manu "man".

Llyr or Lir, divine embodiment of the ‘Tidal Sea’ was depicted as the leader of one of two warring families of gods; according to one interpretation, the Children of Llyr were the powers of darkness, constantly in conflict with the Children of Dôn, the powers of light. In Welsh tradition, Llyr and his son Manawydan, like the Irish gods Lir and Manannán, were associated with the sea. Llyr's other children included Brân (Bendigeidfran), a god of bards and poetry; Branwen, wife of the sun god Matholwch, king of Ireland; and Creidylad (in earlier myths, a daughter of Lludd). Hearing of Matholwch's maltreatment of Branwen, Brân and Manawydan (Manannan) led an expedition to avenge her. Brân was killed in the subsequent war, which left only seven survivors, among them Manawydan and Pryderi, son of Pwyll. Manawydan married Pryderi's mother, Rhiannon, and was thereafter closely associated with them.

Cults of craftsmanship

The insular literatures show that certain deities were associated with particular crafts. Caesar makes no mention of a Gaulish Vulcan, though insular sources reveal that there was one and that he enjoyed high status. His name in Irish, Goibhniu, and Welsh, Gofannon, derived from the Celtic word for smith (Celtic: *Gobanos Divine Smith). The weapons that Goibhniu forged with his fellow craft gods, the wright Luchta or the metalworker Creidhne or Credne (from Celtic *Cerdanos Crafting God), were unerringly accurate and lethal. He was also known for his power of healing by suture, and as Gobbán the Wright, a popular or hypocoristic form of his name, he was renowned as a wondrous builder. Gofannon-Goibniu, as an embodiment of smelting fire formed a rational trinity with the embodiments of carpentry (Luchta the wright) and metallurgy (Creidhne the metalworker). Goibhniu was also the provider of the sacred otherworld feast, the Fled Goibhnenn; he allegedly brewed the special ale thought to confer immortality on those who drank it. In Christian times he became known as Gobbán Saer (Gobbán the Joiner), legendary builder of churches and other structures; as such he is still remembered in modern Celtic folk tradition. His Welsh equivalent, Gofannon, figured in the Mabinogion (a collection of medieval Welsh tales). It was believed that his help being vital in cleansing the plough at the end of the furrows commemorates an ancient ritual in which fire was used to symbolically 'purify' the plough by singeing before further use.

Cults of agricultural gods

Medieval Welsh also mentions Amaethon (from Celtic *Ambaxtonos "great ploughman"), evidently a god of agriculture, of whom little is known.

Cult of terrestrial bounty

Danu, also spelled Dôn or Dana (from Celtic *Danoa ‘Giving Goddess’ ) was the earth-mother goddess or female principle, who was honoured under various names from eastern Europe to Ireland. The mythology that surrounded her was contradictory and confused; mother goddesses of earlier peoples were ultimately identified with her, as were many goddesses of the Celts themselves. Possibly a goddess of fertility, of wisdom, and of wind, she was believed to have suckled the gods. Her name was borne by the legendary Tuatha Dé Danann ("People of the Goddess Danu"), the Irish company of gods, who may be considered either as distinct individuals or as extensions of the goddess and who survive in Irish lore as the fairy folk, skilled in magic.

In Celtic polytheism, the earth-mother was an eternally fruitful source of everything. Unlike the variety of female fertility deities called mother goddesses (q.v.), the Earth Mother is not a specific source of vitality who must periodically undergo sexual intercourse. She is simply the mother; there is nothing separate from her. All things come from her, return to her, and are her.

The most archaic form of the Earth Mother transcends all specificity and sexuality. She simply produces everything, inexhaustibly, from herself. She may manifest herself in any form. In other mythological systems she becomes a more limited figure. She becomes the feminine Earth, consort of the masculine sky; she is fertilized by the sky in the beginning and brings forth terrestrial creation. Even more limited reflections of the Earth Mother occur in those agricultural traditions in which she is simply the Earth and its fertility.

Cult of the power of boggy terrain

Some of Danu's alises, Anu, Anann are apparently derived from the Celtic *Hanona, meaning ‘Bog or Bread Goddess.’ According to classical authors, the Roman Iron Age people of northern Europe offered human sacrifices to celebrate military victories, to gain relief from illness, and to execute people as punishment for crimes. Many of those found in the bogs died violent deaths. Over the past centuries, remains of many hundreds of people--men, women, and children--have come to light during peat cutting activities in north-western Europe, especially in Ireland, Great Britain, the Netherlands, northern Germany, and Denmark. These are the "bog bodies." The individual bog bodies show a great degree of variation in their state of preservation, from skeletons, to well-preserved complete bodies, to isolated heads and limbs. They range in date from 8000 B.C. to the early medieval period. Most date from the centuries around the beginning of our era. We do not know exactly how many bog bodies have been found--many have disappeared since their discovery. Clearly this must have been an aboriginal Pre-Celtic cult that was continued by the Celtic peoples. Bogs were a valuable source of peat, game, herbs, grazing and bog iron but may also have seemed mysterious environments, apparently neither land nor water, where the bodies of the dead were preserved and full of mist and flaring will o’ the wisps with a tendency to make victims of humans who had the misfortune of sinking in the quick mud. The bog then would have seemed to have power over human fortunes and so would have demanded high sacrifices both to redeem the gifts of resources and to appease its apparent anger. Anu may have represented the ambivalent boggy aspect of the earth-mother.

Cult of maternity

One notable feature of Celtic sculpture is the frequent conjunction of male deity and female consort, such as "Mercury" and Rosmerta, or Sucellos and Nantosuelta. Essentially these reflect the coupling of the protecting god of tribe or nation with the mother-goddess who ensured the fertility of the land. It is in fact impossible to distinguish clearly between the individual goddesses and these mother-goddesses, Matres or Matronae, who figure so frequently in Celtic iconography, often, as in Irish tradition, in triadic form. Both types of goddesses are concerned with fertility and with the seasonal cycle of nature, and, on the evidence of insular tradition, both drew much of their power from the old concept of a great goddess who, like the Indian Aditi, was mother of all the gods. Welsh and Irish tradition also bring out the multifaceted character of the goddess, who in her various epiphanies or avatars assumes quite different and sometimes wholly contrasting forms and personalities.

The goddess is the Celtic reflex of the primordial mother who creates life and fruitfulness through her union with the universal father-god. Welsh and Irish tradition preserve many variations on a basic triadic relationship of divine mother, father, and son. The goddess appears, for example, in Welsh as Modron (from Matrona, "Divine Mother") and Rhiannon ("Divine Queen") and in Irish as Boann and Macha. Her partner is represented by the Gaulish father-figure Sucellos, his Irish counterpart Dagda, and the Welsh Teyrnon ("Divine Lord"), and her son by the Welsh Mabon (from Maponos, "Divine Son") and Pryderi and the Irish Angus or Oenghus and Mac ind Óg, among others.

Mother-goddesses were maternal symbols of creativity, birth, fertility, sexual union, nurturing, and the cycle of growth, analogous with figures as diverse as the so-called Stone Age Venuses and the Virgin Mary. Because motherhood is one of the universal human realities, Celtic polytheism was no different from many other socio-religious systems in using some maternal symbolism in depicting its deities. Mother goddesses, as a specific type, were distinguished from the Earth Mother Danu (q.v.), Unlike the mother goddess, who was a specific source of vitality and who was believed to periodically undergo intercourse, the Earth Mother was a cosmogonic figure, the eternally fruitful source of everything. In contrast, mother goddesses were individual, possessing distinct characters, young, and non-cosmogonic, and highly sexual. Although the male played a relatively less important role, being frequently reduced to a mere fecundator, mother goddesses were usually part of a divine pair, and their mythology narrates the vicissitudes of the goddess and her (frequently human) consort, as with Rhiannon and Pwyll.

The essential moments in the myth of the mother goddess is her disappearance and reappearance and the celebration of her divine marriage. Her disappearance had cosmic implications: decline in sexuality and growth. Her reappearance, choice of a male partner, and intercourse with him restored and guaranteed fertility, after which the male consort is frequently was set aside and sent to the underworld to be replaced the next year (this has led to the erroneous postulation of a dying-rising deity).

The other major form of the mother goddess emphasizes her maternity. She is the embodiment of protection and nourishment of a divine child and, by extension, of all humanity. This form occurs more frequently in iconography—a full-breasted (or many-breasted) figure holding a child in her arms—than in myth.

Cults of femininity & majesty

Other goddesses may be the embodiment of Sovereignty, Youth and Beauty in union with her rightful king, or aged and hideously ugly when lacking a fitting mate.

Cults of cyclicality in nature

There appear to have been divine embodiments of various forms of cyclicality. Arianrhod (from Celtic *Argantorotoa Divine Silver Wheel) seems to have represented astral cyclicality, as manifest in the predictable movements of astral bodies and constellations. Thirdly, another deity, sometimes masculine as Aericurius, or feminine as Aeracura, Heracura or Aericura (from Celtic *Haerecura Divine Pastoral Cycle) is known to have been concerned with the earth and underworld and so may have embodied the believed cyclicality of life, death, reincarnation and rebirth as taught by the druids.

Cult of the trinitarian war-goddess

Goddesses may be the embodiment of perceived Dreadful Majesty, like the fearsome war-spirit Morrígan, or of Martial Conflict. like the Badhbh Catha or Badb ("Scald-crow of Battle"), whose name is attested in its Gaulish form, Catubodua, in Haute-Savoie, or the lovely otherworld visitor who invites the chosen hero to accompany her to the land of eternal youth. Irish tradition depicts these as in a trinity of ‘Martial Conflict’ (Badhbh Catha, Catubodua), along with ‘Horse power’ (Macha-Epona-Rhiannon), ‘Dreadful Majesty’ (Morrigan), and ‘Venomous Enmity’ (Nemain). It will be noted that this list contains more than three goddesses, but this confusion is also present in the early modern Irish literary sources. There are other goddesses, as well, who are counted in various sources as part of this "trinity", including Fea and Anann among others. A great slaughterer of men, the ‘Dreadful Majesty’ that was the Morrígan (from Celtic *Mororiganis ‘Nightmare Queen’) , also called Black Annis. Though the etymology is unclear (and possibly incorrect), some trace her survival in Arthurian legend as Morgan le Fay. The name Nemain, symbol of ‘Venomous Enmity,’ derives from Celtic *Namanta ‘Enemy Goddess.’

Cults of fluvial water

As arteries of life-giving water, rivers were often seen as manifestations of nourishing mother-goddesses, such as the Sequential Fluvial Water of the Seine (Sequana, *Sepana) and the Mothering Fluvial Water of the Marne (Matrona) in Gaul, or the Boyne (Boann) in Ireland. Many rivers were called simply Devona, the Divine (Water).

Cult of the stag’s vitality

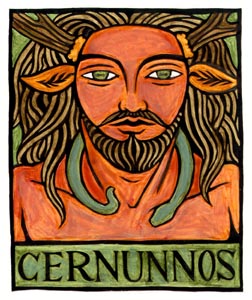

The rich abundance of animal imagery in Celto-Roman iconography, representing the deities in combinations of animal and human forms, finds frequent echoes in the insular literary tradition. Perhaps the most familiar instance is the deity, or deity type, known as Cerowain (from *Cervanios, Stag-God) or Cernunnos, (either from Celtic *Carnonos, Deer-Hoofed One or *Cornonos Horned One ) even though the name is attested only a few times, on a relief at Notre Dame de Paris (currently reading ERNUNNOS, but an early sketch shows it as having read CERNUNNOS in the 18th century), an inscription from Montagnac (αλλετ[ει]υος καρνονου αλ[ι]σο[ντ]εας, "Alleteinos [dedicated this] to Karnonos of Alisontia"; Recueil des Inscriptions Gauloises I (1985), pp.318-325), and a pair of identical inscriptions from Seinsel-Rëlent ("Deo Ceruninco"; L'Année Épigraphique 1987, no. 772). (There is also a libellus from Dacia which mentions a "Jupiter Cernenus", but this may be unrelated.) The interior relief of the Gundestrup Cauldron, a 1st-century-BC vessel found in Denmark, provides a striking depiction of the antlered Cernunnos as "Lord of the Animals," seated in the yogic lotus position and accompanied by a ram-headed serpent; in this role he closely resembles the Hindu god Siva in the guise of Pasupati, Lord of Beasts. The god seems to represent the vitality of stags or of horned male mammals in general, to which warriors aspired. Interestingly, the English word horniness connotes not only being adorned with horns, but also with sexual potency, a natural token of vitality and creativity. Likewise, the word stag connotes in English not only a male cervid, but also a sexually successful male. There may have been a similar linguistic motivation behind his name in Proto-Celtic.

An archaic and powerful deity, widely worshipped as the "lord of wild things." Cernunnos may have had a variety of names in different parts of the Celtic world, but his attributes were generally consistent. He wore stag antlers and was sometimes accompanied by a stag and by a sacred ram-horned serpent that was also a deity in its own right. He wore and sometimes also held a torque, the sacred neck ornament of Celtic gods and heroes. The earliest known depictions of Cernunnos were found at Val Camonica, in northern Italy, which was under Celtic occupation from about 400 BC. Cernunnos was worshipped primarily in Gaul, although there are also traces of his cult in Britain.

An alternate interpretation of the meaning of the Stag-God holds that he represents the power of crossing boundaries, whether those boundaries are between physical locations or concepts. This helps to explain his apparent role as a god of commerce (he is often shown with a cornucopia overflowing with coins,) as well as his attributes of androgyny and therianthropy. If this interpretation is correct, he may be equivalent to the insular maritime deity (see above.) The fact that he possesses antlers rather than horns also seems to be a clue toward this interpretation (antlers, unlike horns, are shed on a seasonal basis.)

Cult of the bullish vitality

Another prominent zoomorphic deity type is the divine bull, the Donn Cuailnge ("Brown Bull of Cooley"), which has a central role in the great Irish hero-tale Táin Bó Cuailnge ("The Cattle Raid of Cooley") and which recalls the Tarvos Trigaranus ("The Bull of the Three Cranes") pictured on reliefs from the cathedral at Trier, .Germany., and at Nôtre-Dame de Paris and presumably the subject of a lost Gaulish narrative. Other animals that figure particularly prominently in association with the pantheon in Celto-Roman art as well as in insular literature are boars, dogs, bears, and horses. The god seems to have been the embodiment of perceived Bullish Vitality to which warriors aspired.

Cult of horse power and horsemanship

The horse, an instrument of Indo-European expansion, has always had a special place in the affections of the Celtic peoples. The goddess Epona, whose name, meaning "Divine Horse" or "Horse Goddess," epitomizes the religious dimension of this relationship, and was a pan-Celtic deity. Her cult was adopted by the Roman cavalry and spread throughout much of Europe, even to Rome itself. She seems to be the embodiment of Horse power, or Horsemanship perceived as a vital power for the protection and welfare of the tribe. She has insular analogues in the Welsh Rhiannon and in the Irish Édaín Echraidhe (echraidhe, "horse riding") and Macha, who outran the fastest steeds.

The Welsh manifestation of the Gaulish horse-goddess Epona and the Irish goddess Macha, *Rigantona 'Great Queen,' (Rhiannon), is best-known from The Mabinogion, a collection of medieval Welsh tales, in which she makes her first appearance on a pale, mysterious steed and meets King Pwyll, whom she marries. Later she was unjustly accused of killing her infant son, and in punishment she was forced to act as a horse and to carry visitors to the royal court. According to another story, she was made to wear the collars of asses about her neck in the manner of a beast. In Irish versions of her cult, ‘Horse power’ (Macha) forms a trinity with ‘Martial Conflict’ (Badhbh Catha) and ‘Venomous Enmity’ (Nemain), often each known individually as an Mor-Ríoghain ("Queen of Phantoms".) Macha, the Irish name for Epona, is mentioned as one of three war goddesses, who were also referred to as the three Morrígna. As an individual, Macha was an example of a class of goddesses with similar attributes, including Badhbh Catha (also known as Badb "Crow," or "Raven"). Inasmuch as ‘horse power’ was a part of and determined martial earthly affairs, Macha was the great earth mother, a ruthless female principle and a great slaughterer of men.

The effect of Christianity

The conversion to Christianity had inevitably a profound effect on this socio-religious system from the 5th century onward, though its character can only be extrapolated from documents of considerably later date. By the early 7th century the church had succeeded in relegating the druids to ignominious irrelevancy, while the filidh, masters of traditional learning, operated in easy harmony with their clerical counterparts, contriving at the same time to retain a considerable part of their pre-Christian tradition, social status, and privilege. But virtually all the vast corpus of early vernacular literature that has survived was written down in monastic scriptoria, and it is part of the task of modern scholarship to identify the relative roles of traditional continuity and ecclesiastical innovation as reflected in the written texts. Cormac's Glossary (c. 900) recounts that St. Patrick banished those mantic rites of the filidh that involved offerings to demons, and it seems probable that the church took particular pains to stamp out animal sacrifice and other rituals grossly repugnant to Christian teaching. What survived of ancient ritual practice tended to be related to filidhecht, the traditional repertoire of the filidh, or to the central institution of sacral kingship. A good example is the pervasive and persistent concept of the hierogamy (sacred marriage) of the king with the goddess of sovereignty: the sexual union, or banais ríghi ("wedding of kingship"), that constituted the core of the royal inauguration seems to have been purged from the ritual at an early date through ecclesiastical influence, but it remains at least implicit, and often quite explicit, for many centuries in the literary tradition.

No comments:

Post a Comment