Ara the Handsome

Recent researches and discoveries have proven that the legend of Ara, although subjected to many transformations, until the 4th and 5th centuries A.D., has its origin in Indo-European mother-sources. The Christian Armenians of the 5th century, took Ara as a man-hero, while the Armenians of the 3rd century, still pagan, had regarded him a god-like personality, or even a god.

Sammuramat is the Assyrian form of Shamiram. Erroneous statements are made by national and foreign historians, about Ara and Shamiram.

Aramis, not Barzanes, as Diodorus says, ruled Armenia at the time of the expedition of Ninus. Aramis, the king of Urartu, had formed a powerful federation of the kinglets of Armenia. He was defeated, but his successors carried on the resistance, and assured the recovery of independence for a considerably longer time.

The first mistress of Ara was an Armenian goddess: The three great ones were Nané (Sumerian-Babylonian, the Athena), Anahit, Astghik.

The ideology greatly developed in the Armenian paganism has no Avestic trait, because the ideal had no place in the Mazdeism, while in the Armenian temples of Armavir statues were erected in honor of the sun and the moon. Some scholars think to have discovered the worship of Triad (trinity) in the Armenian paganism. The edict of king Trdat, invoking Aramazd, Anahit and Vahagn, as the sources of power, and the existence in Ashtishat of the three famous temples, support this theory. The Urarteans also had three great gods — Haldis, Thiespas and Artemis. The same may be said of Zoroastrianism; Artashes cites three gods: Aramazd, Anahit and Mihr. Triad was recognized also by Semitics.

Anahit

Anahit's worship, probably borrowed from the Persians, was of paramount significance in Armenia. Iranians had no idol-worship in the beginning, but Artashes erected the statues of Anahit, and promulgated orders to worship them. The historian Berosus identifies Anahit with Aphrodite, while the Armenian mythology identifies her with the Greek Artemis. According to Strabo, Anahit's worship was dedicated to prostitution, while king Trdat extolls the "great Lady Anahit," the glory of our nation1 and vivifier . . .; mother of all chastity, and issue of the great and valiant Aramzd. Anahit-worship was established in Eriza, Armavir, Artashat and Ashtishat. A mountain in Sopheren district was known as Anahit's throne (Athor Anahta). The entire district of Eriza, the Akilisene (Ekeghiats), was called "Anahtakan Gavar."

The temple of Eriza was the wealthiest and the noblest in Armenia, according to Plutarch. During the expedition of Antony, the statue was broken to pieces by the Roman soldiers. Pliny the Elder gives us the following story about it: The Emperor Augustus, being invited to dinner by one of his generals, asked him if it was true that the wreckers of Anahit's statue had been punished by the wrathful goddess. "No!" answered the general, "on the contrary, I have to‑day the good fortune of treating you with one part of the hip of that gold statue."

The Armenians erected a new golden statue of Anahit in Eriza, which was worshipped at the time of St. Illuminator. Religious prostitution, if it had existed at some previous period, seems to have been suppressed before that date.

The annual festivity of the month Navassard, held in honor of Anahit, was the occasion of great gatherings, attended with dance, music, recitals, competitions, etc. The sick went to the temples in pilgrimage, asking for recovery. The great king Artashes, taken ill, had sent an official to ask the goddess' help, but the king died before the return of the pilgrim messenger.

Mihr

Mihr or Mithra is the genius of the light of heaven and the god of truth. Derjan (Derzana) was the district where the Armenian Mithra worship was centered. Its famous temple was in the sacred village of Bagaritch. The Armenian Mithra does not seem to have become as prominent in Armenia as in Persia. Nevertheless, his name occurs frequently as a component part of many proper names, such as Mihran, Mihrdat, Mehruzhan, while the Armenian Mehian, a pagan temple, idol, altar, has also been traced to the same source. The Christian fire-festival of the Armenians is celebrated in February, a month dedicated to Mihr, and named — Mehekan. The Persian kings received a tribute of 20,000 steeds from Armenia on every festival of Mithra. Of all the Iranian deities, the cult of Mithra alone was diffused among western nations, and it waged stiff resistance against Christianity, but his vigor was exhausted in the fourth century.

Tir

The temple of Tir was a seat of oracles, as interpreter of dreams and defender of arts and letters. Tir was called the Scribe of Armazd, and disclosed the meaning of dreams as oracles. It was identified with both Apollo, the inspirer of divinations, and with Hermes, the messenger of the gods, inventor of the lyre, patron of eloquence and public treaties. One of the ancient Armenian months was called Tré, and several proper names are formed with Tir, such as Tirots, Tiran, Trdat, etc.

Tir, as an epithet of Scribe was believed to have the duty of registering the names of those about to die; hence the joke: "May the Scribe take you away" (Groghe dani kez).

Patriarch Eghishé Tourian finds connection between the pagan custom of obtaining new fire — the Ormizd fire — on New Year's eve, with Christian Candlemas, on which day, until recently, the Armenians used to build fire in the courtyard of the house, and enjoy dancing frolics around it. The Church festival, the Candlemas, is the transformation of the old Terentas, Persian Direndaz (bowman).2

Astghik-Astlik

Astghik was second to Anahit in the rank of adoration among p303the Armenians. Her principal seat was in Ashtishat (Taron), where her chamber was dedicated to the name of Vahagn, that personification of a sun-god, her lover or husband according to popular tales.

Astghik, as the goddess of love, corresponds to the Greek Aphrodite. The rose among flowers and the dove among the birds were her favorites. Astghik's festival — the Vardavar — was celebrated at the commencement of summer. It now corresponds to the Christian Transfiguration, on which day the Armenians still hold some pagan, such as sprinkling water on each other, flying pigeons and playing games, etc. The word Astghik, meaning "little star," is the translation of the name of the Syrian goddess Beldi. A chapel was built by the Illuminator instead of the pagan sanctuary of the three gods — Anahit, Vahagn and Astghik — collectively called Vahévahian. It is now commemorated on the third Sunday of Easter, the "Sunday of the world-church" (ashkharhamadran Kiraki). According to a local tale, Astghik was in the habit of taking a bath in a stream every night; some romantic young men eager to see the goddess' exquisite beauty, lit a big fire on a nearby hill, but Astghik, in order to frustrate their design, caused the entire area, the plain of Mush, to be covered by a fog. Hence the name of Mush, which means mist, in Armenian — Mshoush.

Nané or Nanea

Nané, the daughter of Aramazd, was identified with the Greek Athenas-Pallas, the goddess of war and victory. She was recognized also in the old Iranian religion. The idol of Nané had been brought into Armenia and placed at the bourg of Til by Tigran the Great. Its worship seems to have been confined to that area alone. Its treasures, together with that of the altar of Anahit, were turned over by St. Gregory the Illuminator, to the holy service of the churches of God. The cult of Nané was of Elamite origin. "The story that Nané conceived miraculously, shows that the Mother Goddess of Phrygia herself was viewed, like other goddesses of the same primitive type, as a Virgin Mother," says Frazer.

Barshamin or Barshimnia

This was one of the idols transported by Tigran from Mesopotamia into Armenia, and housed in the village of Thordan, in Daranaghi. The brilliantly white idol was made of ivory and crystal, wrought with silver.

p304 The name Barshamin is derived from the Phoenician Ba‑al‑shamin, in Aramaic form, meaning "lord of heavens," like the Bel of the Babylonians.

Vahagn

Vahagn, as national god, soon found himself at the side of Aramazd and Anahit with whom he founded a "triad." When Zoroastrian ideas were pervading Armenia, superseding the gods of the country, there was so much vitality in Vahagn's worship that Mithra himself could not obtain a firm foothold in that land, in the face of the popularity of his native rival.

Historian Khorenatsi's report of an ancient song gives a clue to his nature and origin:

In travail were heaven and earth, In travail, too, the purple sea! The travail held in the sea the small red reed. Through the hollow of the stalk came forth smoke, Through the hollow of the stalk came forth flame, And out of the flame a youth ran! Fiery hair had he, Ay, too, he had flaming beard, And his eyes, they were as suns! |

Other parts of the song, now lost, said that Vahagn fought and conquered dragons, hence his title Vishabakagh, "dragon reaper." He was invoked as a god of courage, later identified with Herakles. He was also a sun-god, rival of Baal-shamin and Mihr.

The Vahagnian song was sung to the accompaniment of the lyre by the bards of Goghten (modern Akulis), long after the conversion of Armenia.

The stalk or reed, key to the situation, is an important word in Indo-European mythology, in connection with fire in its three forms.

The name, originally Verethragna, the god of victory in Avesta, turned into Varhagn (the Zendic th becoming h in Arsacid Pehlevi), later on to take the form of Vahagn.

Vahagn was identified with the Greek Heracles after the latter's image was brought into Armenia by Tigran the Great. The priests of Vahévahian temple, who claimed Vahagn as their own ancestor, placed the statue of the Greek hero in their sanctuary. All the gods, according to the Euhemerian3 belief, had been living men; Vahagn likewise, was introduced within the ranks of the Armenian kings, as the son of Erouand (6th century B.C.), together with his brothers — Bab and Tiran. In the Armenian translation of the Bible, Heracles worshipped at Tyr, is named Vahagn.

Gissaneh (Kissaneh) and Demeter-Demetr

Agathangelos ignores the existence of these two idols in Taron. On the other hand, there must have been some ground for the tale about the fierce struggle of paganism, as reported by Hovhan (John) Mamikonian who lived in the seventh century.

Sandaramet

Sandaramet (Spenta Armaiti), one of the seven Amshaspents (the archangels), of the Mazdeian religion, was the daughter of Ahuramazda, representing the divine type of the virtuous woman. She was the spirit of piety and modesty.

The Armenian translator of the two apocryphal books of the Maccabees has identified Spandaramet with Dionis (Bacchus), a fact leading to the presumption that Spandaramet was regarded in Armenian paganism not as a goddess, but a masculine deity, lacking the moral traits of the Mazdeian Amshaspent. Being, in Avestic concept, the Spirit or the embodiment of the earth, Spandaramet, in the form of Sandaramet, became synonymous with earth, especially the underworld or hell. The word, in the form of Sandarapet, later on, came into use, meaning the chief or god of the hell.

The relation of this deity with Bacchus, the god of wine, is explained by the fact that wine, the most excellent product of earth, was an indispensable element in the mysteries of pagan festivals. Hence, the god presiding over the nightly drinking bouts would certainly have his lewd votaries male and female, — the bacchants and the bacchantes.

National and Foreign Gods

Nature-worship, such as the adoration of the sun and stars, was older in Armenia than the idol-worship. The statues of the sun and moon, erected in Armenia, as reported by Khorenatsi, should be classified among national idols, in the opinion of H. Gelzer. The seven temple-altars, the pantheon of the Armenian deities, seem to have been located in Bagavan (the town of gods), where the great national festival was celebrated in pomp, at the beginning of New Year, on the advent of the month of Navassard (New Year). Some writers erroneously believed that this celebration took place in Ashtishat or Vagharshapat.

Iranian influence

The ancient Armenian religion was a form nearer to that of the Arsacid-Parthian kings. From that source have been borrowed the following:

Armazd, without its distinctly Iranian features.

Mihr-Mithra.

Spandarmet-Spenda-Aramaiti.

Vahagn-Verethragna.

Tir or Ture-Tir.

Anahit-Nahit.

These gods were not worshipped in Armenia, in the sense of their Iranian prototypes, there being neither Magi nor fire-worship in Armenia. There was no real identity between the old Armenian Pagan cult and the Sassanian Mazdeism, considering that the doctrine of Zoroaster was not in favor of idols.

Hellenic influence

Idols were introduced into Armenia through Hellenic influence. Greek statues and even temple-priests were transported there by Artashes and Tigran the Great. The following are the gods of Armenia, identified as of Greek origin by the Greek translation of Agathangelos:

Aramazd — Zeus-Pater or Jupiter.

Mihr-Hephaestus.

Anahit-Artemis.

Nané-Athena.

Astghik-Aphrodite.

Tir-Apollo-Vahagn.

Vahagn-Heracles.

Syrian influence

The deities of Syrian origin were:

Barshamin.

Astlik (Astghik).

Nané.

It was a custom among the Armenians to go on pilgrimage to the Syrian mother-goddess, Tharada, at Herapolis, offering her precious stones. The Armenian word kourn (pagan priest) is of Syrian origin.

Heroes and Legends

Artavazd.— The life of Artavazd, the son of Artashes, is wholly legendary; those legends were partly collected by Khorenatsi from the songs of bards and probably also from the records of the chief-Priest Oughub (Olympius). Artavazd's role has been one of fierce struggle against the Median tribe (the Mar) and their chief Arcam or Arcavan. Tigran the son of Erouand, is said to have killed Azhdhak, the king of the Medes, the grandfather of Cyrus, carried away his wife, Anoush and children into Armenia, and settled them at the foot of Mount Ararat.

This family was known in popular songs of the ancient era as Vishabazounk — the issue of dragons, because "Azhdahak means dragon in our language" says Khorenatsi. The progeny of the dragon, as related in the songs of the Goghten Canton, stole the child Artavazd, an implacable enemy of the Vishabazounk, now represented as demons, persecuted them relentlessly, to the point of extermination of the race.

Yeznik, the Armenian erudite and theologian of the fifth century, relates that, according to old tales, Artavazd was "detained by demons and is still alive, and that he will some day come out and dominate the world." Yeznik adds, "the infidels (the idolators of Armenia) cling to the superstitious hopes, like the Jews, who are bound to the expectation that David is to come, to construct Jerusalem, to gather together the Jews, and to reign over them."

Artavazd, a killer of dragons and their race, could not have been a person of vicious or demented type. His wars against the Mar people, or the dragons, remind us of the struggle which Feridun wages against the demons of Mazandaran, whose people, like the Mari colony of Ararat, were the issue of a foreign and savage tribe.

The Avesta4 mentions Ahavazdah (= Artavazd), an "immortal" personality, fighting a wild tribe of Touranian origin. J. Darmesteter referring to this says that in the Armenian legend-songs, there is a king, Artavazd, who cannot die. Could not the immortal Ashavada have been adopted in Armenia? Patriarch Tourian answers the question of the French orientalist, by stating that Artavazd can positively be identified with the Ashavazd of the Avesta, who, as one of the undying souls, will wake from his sleep, to re-organize the world, and to carry out the work of Salvation, the miraculous work of Frashokereti (hrashakert in the Armenian).

The Avesta has also the tale of Azhidahaka, the evil spirit, killed by Thraetaona (Feridoun). From this story their springs the one of Zohak, the tyrant, the same Azhdahak finally became identified with Azhdahak (of Khorenatsi), the grandfather of Cyrus who was killed by our Tigran Erouandian in the fifth century B.C. According to Khorenatsi, "Persian worthless and foolish fables relate that a certain Feridoun (Hrouten) bound Purask-Azhdahak in bronze fetters and carried him to the Demavend mountain (in Tabaristan); that Feridoun fell asleep on the road and was dragged by Pursab to the hill; that Feridoun, awakening, carried Purasb into a cave of the mountain, chained him and placed himself before him as a barrier, where he still remains, with no power to devastate the world. A similar tale existed about Artavazd, with the addition that watchmen incessantly strike at the anvil, in order to remind us of the assurance that ironmongers harden the links of the chain.

According to a tale until recently prevalent among the Armenians, Mehr (Mihr), an intercessor deity, devoted to the work of redemption, had to be detained and chained in fetters.

Shamiram (Semiramis) and Ara the Handsome

The date, even the existence of Shamiran have been matters of conjecture among the scholars. Some of them put her as far back as 2000 B.C. as the wife of Ninus, the founder of Nineveh; others bring her down to the fourteenth or eighth or sixth centuries B.C.

Prof. Lehmann-Haupt, by putting together the results of archaeological discoveries, has arrived at the following conclusion: Semiramis was, probably, a Babylonian, for it was she who imposed the Babylonian cult of Neb or Nebu upon Assyrian religion. On a column discovered in 1909, she is described as "a woman of the palace of Samsi-Adad, king of the world, king of Assyria . . ., king of the Four Quarters of the World." Ninus was her son. The dedication shows that Semiramis occupies a position of unique influence. She waged war against the Medes and the Chaldeans. The legends probably have a Median origin.

Avoiding marriage, in order not to lose the power, she selected the attractive young men of the army, made love with, and destroyed them. This story is parallel with the Babylonian (Sumerian?) fiction, where Gilgamesh, the hero, rejects the goddess Ishtar, who had murdered all her lovers.

Popular etymology which connected the name of Semiramis with the Assyrian Summat, "dove," seems to have first started the identification of the historical Semiramis with the goddess Ishtar and her doves. Her irresistible charm and sexual excesses (belonging only to the legends), and other features of the story, all bear out the view that she is primarily a form of Astarté.

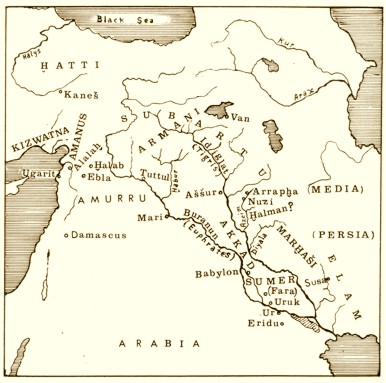

The stories concerning Semiramis were later transported to Armenia. To her is ascribed the founding of Van, which tell of the enterprises of Menuas, Argistis and others, but do not mention any Shamiram, while every stupendous work of antiquity by Euphrates or Iran, seems to have been attributed to her.

The legend about the marriage proposed to the Armenian king Ara the Handsome, the rejection, and his death in the ensuing battle, are, partly, variants of the fiction of the Babylonian hero, Gilgamesh. Similar to them are the tales of Aphrodite and Adonis, and Cybele and Addis. In both cases the victims of the goddesses had been brought back to life by their killers. The temple at Zela, Anatolia, dedicated to Anahit, was built on a knoll, called Semiramic. Such hillocks as that one were, traditionally, the graves of the lovers of Shamiram.

Ara regained life, tradition says, at the village of Lezk, by the genii who licked his wounds. The village, situated near Van, on an eminence, had had a pagan temple, later replaced by the chapel of the All-Saviour (Amenaprkitch). Some connection is said to exist between the same Lezk, and the Armenian word lizel meaning to lick, caress with the tongue.

In the Armenian literature, Ara often has been depicted as a model husband, who, despite threats and allurements, remained loyal to his consort Nouard, setting a royal example to marital happiness, p310and confirming the traditional virtues in the Armenian family life.

Haik and Bel

Haik is regarded as the eponymous ancestor of the Armenian people. Bel or Belus, supreme god of the Babylonians and Assyrians, is identified with Nimrod or Neprot, who "was a mighty hunter before the Lord." (Gen. X.9). . . . Neprot demanded that he should be worshipped, but Haik, "brave and famous among the mighty," (in the words of Khorenatsi), disobeyed Bel, and departed with his family from Babylon toward the north, to Ararat. Bel followed him with an army, was engaged in war, and killed by Haik. This name became synonymous with "mighty one, the powerful, the athletic," haikapar, an adverb in the sense of mightily, heroically.

In the Armenian translation of the Bible, the constellation Orion is called Haik. "For, the stars of heaven and of Orion shall not give their light," (Isaiah, 13.10). "Canst thou bind the sweet influence of Pleiads, or loose the bands of Orion?" (Job, 38.31).

The canton of Hark in Armenia, where the family of Kaik or his predecessors, the "House of Thorgom" had settled, according to Khorenatsi, was also the place where the tyrant Bel was buried. The name Hark, meaning 'Fathers' in Armenian, had led ancient writers to certain conclusions, which are now contested. Some authorities believe that Hark is another form of Erech, one of the four cities founded by Nimrod. "And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar," (Gen. 10.10). Erech in cuneiform inscriptions, Uruk or Arku, is the modern Varka, situated south-east of Babylon. Due to the multitude of ancient graves, the place was once regarded by Persians as a holy necropolis — city of the dead.

The story about Haik and Bel, Vahagn and Barsham of Syria, and Aram and the Barsham of Babylon, are the different phases of victorious struggles against Assyria and Babylon, by the forces of Aramé and other Urartean kings. They were also the echoes of the successful wars conducted against the Medes or the Mari, by Artashes (Artaxias) and Tigran the Great.

Notes:

1 "The human race" is what the king meant.

2 Armenian Diarnentaratch.

3 From Euhemeros, a Greek philosopher of the fourth century B.C. His theory held that the gods of mythology were but deified mortals.

4 The sacred book of the ancient Zoroastrian religion.

By Vahan M.Kurkjian, "History of Armenia", Chapter XXXIV.

.